Suzanne ElvidgeAugust 29, 2024

Tag: Patient-centricity , clinical trial design , product design

While drugs and devices will actually be used by patients, the focus of the drug development process has more often been on the requirements of regulatory bodies, the needs of the healthcare professionals and the income for the shareholders. This drives a focus on patient safety, clinical trial outcomes, patient confidentiality and return on investment, with patients receiving only limited information. This makes their only role in the study that of participant. [1] However, as patients are the real end users of the drugs and devices, drug developers need to put them at the heart of the study – this is patient-centricity.

Patient centricity, which is relevant to both drug development and healthcare, can be defined as: ‘Putting the patient first in an open and sustained engagement of the patient to respectfully and compassionately achieve the best experience and outcome for that person and their family.’ [1] This is not only about doing the right thing – which is of course vitally important – it’s also about making clinical trials more efficient and cost-effective. More efficient clinical trials mean that drugs are more likely to get through the regulatory process and onto the market, therefore improving the return on investment for biopharma companies. Drugs developed with patient-centricity in mind are more likely to be taken by patients, therefore bettering their short- and long-term outcomes. These improved outcomes help society and make healthcare systems more cost-effective.

Getting drugs through clinical trials is a major hurdle in the route to market, as the failure rates for candidates passing through phase I to III studies can be as high as 90%. [2] One of the reasons that trials fail is participant retention, as up to 40% of participants can drop out before the trial is completed. [3] This increases the number, length or size of trials required to get sufficient high-quality data for approval.

There are a number of approaches to improving the patient-centricity in clinical trials: decentralising studies, using adaptive clinical trial designs, optimising dosing, leveraging personalised medicine and incorporating quality of life endpoints. [4]

One of the challenges to recruiting patients to clinical trials in the first place, or to retaining them through to trial completion and follow up, is the number of site visits required and the location of the sites. The time to travel to central clinical trial sites may be long, sites may be hard to access for people who rely on public transport, and there are additional challenges for older people, neurodiverse people, people from the LGBTQIA+ community and people from ethnically minoritised groups. Moving to virtual clinical trials takes away many of these barriers. Virtual studies reduce costs by cutting the need for travel reimbursement, decreasing the investment required in sites and staff and speeding up participant enrolment. Better recruitment and retention means a reduced risk of trials having to be expanded or repeated. [4-10]

The randomised controlled trial (RCT) has been the gold standard for drug development for many years. In these, patients are randomised to a treatment or control arm. However, the inclusion and exclusion criteria are often very strict, resulting in low levels of diversity in the study population, as well as data that may not represent the general population. The studies can also be lengthy, increasing the risk of participant drop-out. [11-13] Adaptive clinical trials, where researchers conduct interim data analyses throughout the study and make changes based on the results, are more flexible. As an example, a decision may be made to drop an ineffective treatment, reduce patient visits or finish a trial earlier, making the experience easier for participants. [4, 12]

Dose-finding clinical trials, particularly in oncology, can involve patients receiving the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of a drug, which may mean that patients experience severe side effects. By optimising the dosing, patients have a better experience and researchers can still learn about the drug efficacy. [4]

Personalised medicine – treatments tailored to a patient’s genetic makeup – allows participants to receive therapeutics that are more likely to be effective, or have fewer side effects. This approach also allows companies to run smaller clinical trials. While the challenge associated with this kind of trial is that the patient pool is likely to be smaller, researchers can use data from real world evidence (RWE), patient registries, medical records and other databases to supplement the trial results. [4]

Patient-centric trials often have a greater focus on quality of life (QoL) endpoints, but for these endpoints to be effective and useful, they will need to be designed with a focus on the specific disease and in collaboration with participants and patient groups. The information can be captured with devices supplied by the clinical trial team, or with participants’ own technology (BYOD – bring your own device). [4]

Poor patient adherence to treatment is associated with worsening of disease, a lower quality of life, higher risk of death and higher costs for healthcare. [14] Despite these all having an impact on short- and long-term health outcomes, patient adherence levels remain low. In a 2019 survey of pharmacies, the overall adherence rate in patients with chronic diseases was 59%, with 19% of patients reducing the dose of the medication, having drug holidays or stopping the medication because of concerns about side effects, without telling their healthcare professional. [15]

A range of factors have an impact on adherence, ranging from socioeconomic factors, through access to healthcare, to therapy-related factors such as complexity and duration of treatment, adverse events and patient understanding of the drug/disease. Tackling the therapy-related issues through patient-centric product design is one route to better adherence, which in turn has potential to improve outcomes for patients, their families and for the healthcare system as a whole. Better adherence will also have a positive impact on the company’s return on investment by increasing medication use. [16]

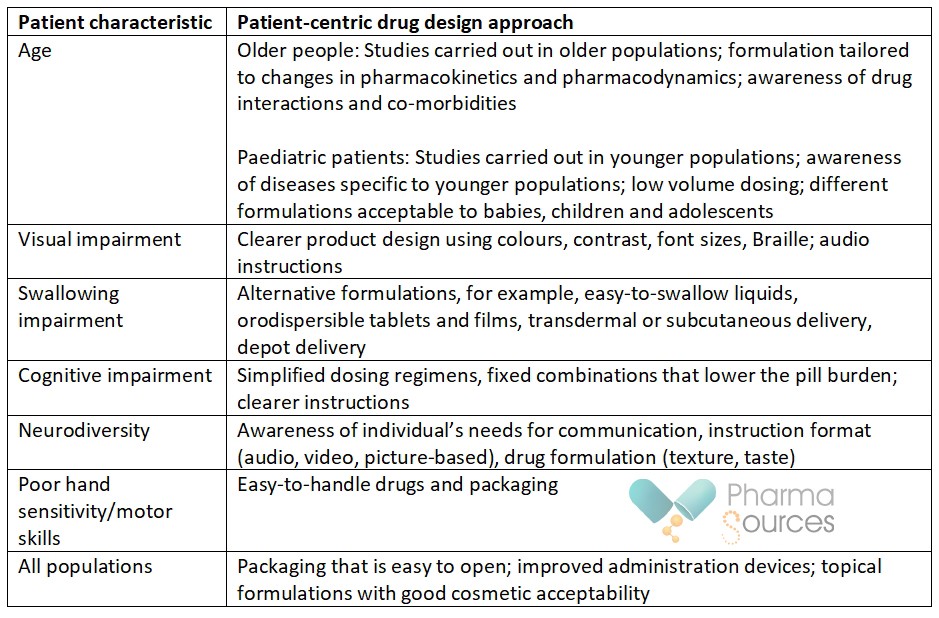

A number of patient-related characteristics have an impact on therapy-related poor adherence, and can benefit from patient-centric drug design: [16]

Creating patient-centric drugs – drugs that are in line with patient preferences – has potential to make significant changes for patients, physicians and healthcare systems by improving short- and long-term outcomes for patients. Understanding what these patient preferences are is key, and this can be achieved by spending time with patients, patient groups, advocates and carers. [17]

1. Yeoman, G., et al., Defining patient centricity with patients for patients and caregivers: a collaborative endeavour. BMJ Innov, 2017. 3(2): p. 76-83.

2. Sun, D., et al., Why 90% of clinical drug development fails and how to improve it? Acta Pharm Sin B, 2022. 12(7): p. 3049-3062.

3. Hutson, M., How AI is being used to accelerate clinical trials. Nature, 2024. 627: p. S2-S5.

4. Ooms, K., The Benefits of Patient Centricity in Clinical Trials: How it can Support Clinical Operations and Study Adherence. IPI Health Outcomes, 2022. 14(2): p. 70-73.

5. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, Health and Medicine Division, Board on Health Sciences Policy, and Forum on Drug Discovery, Development and Translation, Virtual Clinical Trials: Challenges and Opportunities: Proceedings of a Workshop, ed. C. Shore, E. Khandekar, and J. Alper. 2019, Washington (DC).

6. Elvidge, S., Queering clinical research. The Peakwords blog: Writing about science, 27 March 2024. Available from: https://www.peakwords.com/the-blog-writing-about-science/queering-clinical-research.

7. Elvidge, S., Why Diverse Representation in Clinical Research Matters. Pharma Sources: An eye on the biopharma industry, 19 March 2024. Available from: https://www.pharmasources.com/industryinsights/why-diverse-representation-in-clinical-r-76347.html.

8. Adams, B., Sanofi launches new virtual trials offering with Science 37. Fierce Biotech, 2 March 2017. Available from: https://www.fiercebiotech.com/cro/sanofi-launches-new-virtual-trials-offering-science-37.

9. Ranganathan, P., R. Aggarwal, and C.S. Pramesh, Virtual clinical trials. Perspect Clin Re, 2023. 14(4): p. 203-206.

10. Elvidge, S., Decentralising research: Virtual clinical trials. Pharma Sources: An eye on the biopharma industry, 14 May 2024. Available from: https://www.pharmasources.com/industryinsights/decentralising-research-virtual-clinical-76396.html.

11. Monti, S., et al., Randomized controlled trials and real-world data: differences and similarities to untangle literature data. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2018. 57(57 Suppl 7): p. vii54-vii58.

12. Fernainy, P., et al., Rethinking the pros and cons of randomized controlled trials and observational studies in the era of big data and advanced methods: a panel discussion. BMC Proc, 2024. 18(Suppl 2): p. 1.

13. Tysinger, B. and Jakub P Hlávka, Why Diverse Representation in Clinical Research Matters and the Current State of Representation within the Clinical Research Ecosystem, in Improving Representation in Clinical Trials and Research: Building Research Equity for Women and Underrepresented Groups, K. Bibbins-Domingo and A. Helman, Editors. 2022, National Academies Press (US): Washington (DC).

14. Jimmy, B. and J. Jose, Patient medication adherence: measures in daily practice. Oman Med J, 2011. 26(3): p. 155-9.

15. Jungst, C., et al., Medication adherence among patients with chronic diseases: a survey-based study in pharmacies. QJM, 2019. 112(7): p. 505-512.

16. Menditto, E., et al., Patient Centric Pharmaceutical Drug Product Design-The Impact on Medication Adherence. Pharmaceutics, 2020. 12(1).

17. Lester, N., Should your patient centricity include the carer experience? A Life in a Day: Insights, 25 March 2024. Available from: https://alifeinaday.co.uk/2024/03/25/should-patient-centricity-include-carers-experience/.

Based in the north of England, Suzanne Elvidge is a freelance medical writer with a 30-year experience in journalism, feature writing, publishing, communications and PR. She has written features and news for a range of publications, including BioPharma Dive, Pharmaceutical Journal, Nature Biotechnology, Nature BioPharma Dealmakers, Nature InsideView and other Nature publications, to name just a few. She has also written in-depth reports and ebooks on a range of industry and disease topics for FirstWord, PharmaSources, and FierceMarkets. Suzanne became a freelancer in 2006, and she writes about pharmaceuticals, consumer healthcare and medicine, and the healthcare, pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries, for industry, science, healthcare professional and patient audiences.

Contact Us

Tel: (+86) 400 610 1188

WhatsApp/Telegram/Wechat: +86 13621645194

Follow Us:

Pharma Sources Insight January 2025

Pharma Sources Insight January 2025