Suzanne ElvidgeMarch 19, 2024

Tag: Diverse Representation , Ethnicity

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), where study participants are randomly allocated to an experimental group or a control group, became the 'gold standard' of clinical research in the mid-20th century. [1] RCTs have historically enrolled proportionally more white men than people from other groups, with the thinking, at least in part, being that the results could be extrapolated to all populations. Subsequent research, however, has shown that this is not the case, as underrepresented groups may have different responses to the disease or drug, based on social, cultural and other contexts. [2] Diversity in clinical trials, which is about so much more than differences in biology, is therefore an essential part of ensuring that everyone has equitable access to the most effective and safest approaches to treatment.

Using drugs that haven't been tested in certain groups is a gamble. By excluding some people from clinical studies, companies are reducing the possibility of generalising their results to a broader population at launch, and potentially limiting the market (and therefore income) for their drug or device. The lack of diversity in clinical trials can also have a financial impact on healthcare provision, as drugs that are less effective in certain groups can affect quantity of life, quality of life and ability to work. [2] Looking at it from a purely economic perspective, while ensuring that clinical trials are fully diverse in the first place may appear more costly, it could save the cost of redoing studies to reach a wider market at a later date.

Recruitment and retention are a huge challenge for companies running clinical trials, and a lot of time and money is lost when clinical trials fail through lack of participants. Studies looking at clinical trials funded by two UK funding bodies between 1994 and 2002 showed that less than a third recruited the number of patients that they needed, and of those given an extension of time and money, only one in five hit their recruitment target. [3] In an international study, the termination, suspension or discontinuation of over half of Phase I to Phase IV clinical trials between 2011 and 2021 was as a result of low accrual. [4] Repeating trials that fail part way through because of attrition, or restarting trials that didn't hit their recruitment target, is costly, and result in companies losing income as the drugs will either reach the market at a later date, or not reach the market at all.

Recruitment and retention may not appear to have a clear link with diversity, but making changes to clinical trials to improve diversity could have an impact on both initial recruitment and on patient retention. This would save money and time for biopharma companies, as well as speeding access to drugs for patients. Changes can range from understanding the issues in recruitment that go along with ethnicity, through changing criteria for enrolment, to considering the acceptability of the ingredients in the drugs, looking into the accessibility of the clinical trial centre for someone who can't afford a car, or considering the anxiety induced by not being familiar with a clinical trials site.

Race categorises people into groups sharing certain distinctive physical traits. Ethnicity is broader than race. It encompasses racial, national, tribal, religious, linguistic and cultural origins and background. Both ethnicity and race are social constructs, and neither are detectable in the human genome. [2, 5] Lack of representation in clinical research runs the risk of undermining clinical research and its goals. [2]

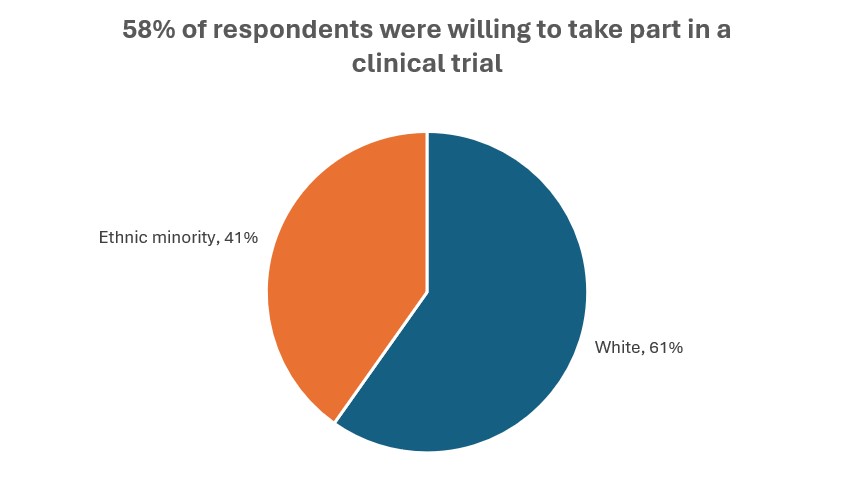

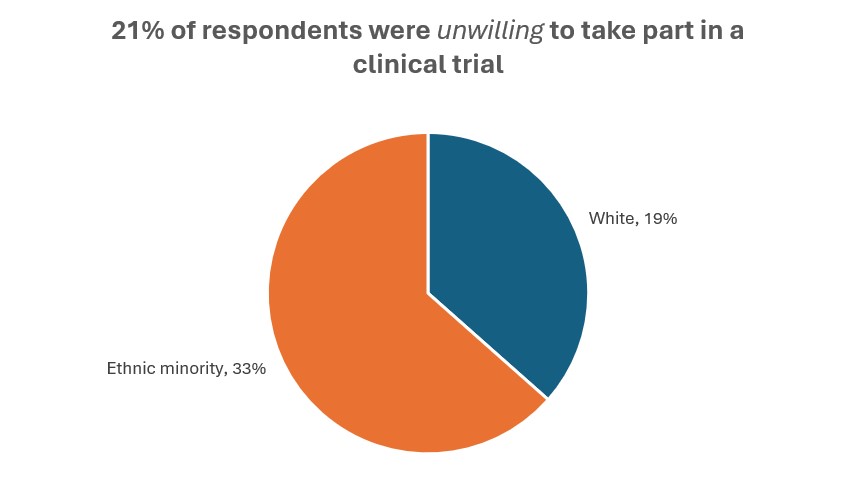

In an analysis of US clinical trials carried out between March 2000 and March 2020, fewer than half reported race or ethnicity data, and 80% of participants were white. [6] In an Ipsos UK survey published in 2024, significantly fewer respondents from ethnic minorities were willing to participate in clinical trials, compared with white respondents, and significantly more said that they were unwilling to participate. While ethnically minoritised adults are more likely to be invited to take part in a clinical trial, significantly fewer will actually take part compared with white respondents. [7]

Source: Ipsos [7]

Source: Ipsos [7]

Poor treatment of people of colour in historic clinical trials, such as the 1932 untreated syphilis study at Tuskegee, in which Black men with syphilis had treatment withheld to study the natural history of the infection, have left ethnically minoritised populations with a distrust of healthcare and of clinical trials. [8] Conversely, the lack of testing of drugs can also mean that these populations are wary of taking their prescribed medications, as they have not been tested on people like them. Poor experiences with the healthcare system, for example the higher rates of maternal mortality in Black and Asian women in the UK, lead to lack of trust in the healthcare system as a whole, which also has an impact on clinical trial uptake. [9]

Working alongside ethnically minoritised people to improve their understanding of the clinical trials process, getting their input, and providing reassurance that changes to research practices have been put in place to ensure that studies like Tuskegee could not happen again, have the potential to improve both uptake and retention.

Simple changes can also make differences, such as ensuring that the drug formulation is acceptable to people with religious or moral food exclusions, allowing the option of family members coming to clinic appointments, and providing translators.

Information and education are key. As shown in the Ipsos survey, only 77% of ethnically minoritised respondents had heard the term clinical trial, compared with 94% of white respondents. One in four of the people from ethnically minoritised backgrounds said that they did not know enough about research or clinical trials to participate, with knowledge being lowest in 65- to 74-year-olds. Materials should be written plainly and clearly, including visual instructions and text in relevant languages, and should emphasise that clinical trials can benefit individuals and their community.

Women are underrepresented in clinical trials. A systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs showed an overall median enrolment rate of women of just 41%. [10] Early stage trials, carried out in healthy volunteers, often focus on people between the ages of 18 and 45 but exclude women with childbearing potential, which means that women can make up as few as 29% of the population. [11] This has had an impact on healthcare for women. [12]

Women are more likely to be care providers, for children or other family members. Clinical trial payments should cover care costs in order to make trials more accessible, or clinical trial sites could look at having on-site care options. [13]

Virtual trials, including processes such as e-consent, telemedicine, electronic clinical outcome assessment (eCOA), remote patient monitoring (RPM) and wearables, supported by direct-to-patient (DtP) shipping of drugs and supplies, alongside virtual and mobile nurses, could widen access to clinical trials for women, older people, and people with access needs and requirements. [4]

As people get older, they are more likely to develop health problems, such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, osteoarthritis, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, depression, dementia and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). [14] Even though this population is more likely to be prescribed drugs, they are underrepresented in clinical trials. [15, 16]

Modifying clinical trial eligibility criteria to include people with well-managed comorbidities would increase the number of people taking part, and make the results more easily generalised to a broader population. [17]

Other barriers to clinical trials for older people include mobility, travel and communication difficulties. Some older people may have cognitive difficulties, and so consent needs to be clear, or proxies may be required to be involved in the decision-making process and to sign consent forms. Older people or people with concomitant disorders may require additional support throughout the clinical trial. [16]

For older people, and for people with other mental or physical health conditions, travel can be exhausting and stressful. Having someone on hand to travel with them or meet them at the bus stop, train station or car park could provide them with confidence and reassurance. [13]

People from the LGBTQIA+ community have faced challenges with accessing healthcare. A Stonewall report found that almost a quarter have witnessed discriminatory or negative remarks from healthcare staff, and one in seven have avoided treatment for fear of discrimination. [18, 19]

Changes that will make LGBTQIA+ people more comfortable about accessing healthcare and clinical trials, will include ensuring that language is specific and inclusive (for example, is the trial looking for women, or for people with a uterus), forms include appropriate gender options, changing rooms and toilets have gender-neutral options, and that LGBTQIA+ staff are supported. [19]

Providing images or video as well as text instructions for access to the clinical trial location will support neurodivergent people and people with anxiety disorders, as it will give them confidence that they can find the site and the specific room. These should also be supplied for all subsequent visits as a reminder. Visuals will also help those for whom English is a second language. Including suggestions for the type of clothing to wear, a list of what to bring, and ideas of what the session will include can also help.

While research in the past has suggested that autism makes people less sensitive to pain, recent studies show that autistic people experience pain at a higher intensity than the general population, are less able to adapt to the sensation, and are more likely to have higher levels of pain-related anxiety. [20-22] It is important to understand this when designing endpoints for clinical trials, particularly subjective endpoints such as patient-reported outcome measures [PROMs]), as well as when evaluating current and past study results.

Truly fixing diversity and accessibility in clinical trials may require taking apart everything we currently do and starting again, but in the meantime, there are a lot of small fixes that can be made. Many of the changes discussed in this piece will make clinical trials more accessible for everyone, not just for those in specific under-represented groups. Other changes that will benefit everyone include:

● Training staff on equality, diversity and accessibility, and making sure that they understand that discrimination will not be tolerated

● Ensuring that people are paid for travel or missed work

● Building in flexibility to clinic visit timings, for example having appointments early in the morning, in the evening or at weekends

● Sharing real-life patient experience from a diverse range of people

● Placing clinics on public transport routes, providing transport for patients, using mobile clinics, or allowing remote assessments

● Getting specialist nurses that know the patient populations involved in study design

● Making sure that the clinical trial burden isn't too onerous - number of clinic visits, length of study

● Talking to patients and ensuring that the endpoints actually reflect what they want from treatment

● Making clinical trials more interesting, for example locating clinical trials at places that people want to go to

● Ensuring that clinical trials make people feel special and feel included

In order to recruit and retain more people from diverse populations and create clinical studies that accurately reflect the general population, companies need to work on trust, or the lack of it. In an Ipsos study, the barriers to participation cited by ethnically minoritised people included lack of trust in the health system, discomfort or lack of trust in clinical trials and research, and location.

While the Ipsos study looked at ethnicity, the findings on education and trust are likely to cross over into other underrepresented groups. People designing clinical trials need to engage with these groups, understand what their barriers and needs are, and enlist their help. This will require building trust by working with individuals and community leaders, and creating focus groups that really listen to people, and take their lived experiences on board.

This piece is based in part on a conversation with Heidi Green, Director of Health Research Equity at COUCH Health.

1. Bothwell, L.E., et al., Assessing the Gold Standard--Lessons from the History of RCTs. N Engl J Med, 2016. 374(22): p. 2175-81.

2. Tysinger, B. and Jakub P Hlávka, Why Diverse Representation in Clinical Research Matters and the Current State of Representation within the Clinical Research Ecosystem, in Improving Representation in Clinical Trials and Research: Building Research Equity for Women and Underrepresented Groups, K. Bibbins-Domingo and A. Helman, Editors. 2022, National Academies Press (US): Washington (DC).

3. Gardner, H., K. Gillies, and S. Treweek, Healthcare's dirty little secret: results from many clinical trials are unreliable. The Conversation, 18 October 2016. Available from: https://theconversation.com/healthcares-dirty-little-secret-results-from-many-clinical-trials-are-unreliable-67201.

4. GlobalData Healthcare, Increased use of virtual trials has contributed to improved trial accrual rates. ClinicalTrials Arena, 12 August 2021. Available from: https://www.clinicaltrialsarena.com/analyst-comment/increased-use-virtual-trials-accrual-rates/?cf-view.

5. Blakemore, E., Race and ethnicity: How are they different? National Geographic, 22 February 2019. Available from: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/race-ethnicity

6. Turner, B.E., et al., Race/ethnicity reporting and representation in US clinical trials: a cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Am, 2022. 11.

7. West, R., Diversity and clinical trials in the UK. Ipsos. 2024. Available from: https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/publication/documents/2024-02/Health%20Equity_Clinical%20Trial%20Research_Feb2024.pdf.

8. CDC. The USPHS Untreated Syphilis Study at Tuskegee. 9 January 2023. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/index.html.

9. MBRRACE-UK. Maternal mortality 2019-2021. October 2023. Available from: https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/mbrrace-uk/data-brief/maternal-mortality-2019-2021.

10. Daitch, V., et al., Underrepresentation of women in randomized controlled trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trials, 2022. 23(1): p. 1038.

11. Cottingham, M.D. and J.A. Fisher, Gendered Logics of Biomedical Research: Women in U.S. Phase I Clinical Trials. Soc Probl, 2022. 69(2): p. 492-509.

12. Liu, K.A. and N.A. Mager, Women's involvement in clinical trials: historical perspective and future implications. Pharm Pract (Granada), 2016. 14(1): p. 708.

13. Greiner, A., 3 Practical Ways to Encourage Women's Clinical Trial Participation. BioSpectrum Asia Edition, 1 March 2024. Available from: https://www.biospectrumasia.com/opinion/121/23843/3-practical-ways-to-encourage-womens-clinical-trial-participation.html.

14. NCOA, The Top 10 Most Common Chronic Conditions in Older Adults. Chronic Conditions in Older Adults, 31 August 2023. Available from: https://www.ncoa.org/article/the-top-10-most-common-chronic-conditions-in-older-adults.

15. Herrera, A.P., et al., Disparate inclusion of older adults in clinical trials: priorities and opportunities for policy and practice change. Am J Public Health, 2010. 100 Suppl 1(Suppl 1): p. S105-12.

16. Pitkala, K.H. and T.E. Strandberg, Clinical trials in older people. Age Ageing, 2022. 51(5).

17. Unger, J.M., et al., Association of Patient Comorbid Conditions With Cancer Clinical Trial Participation. JAMA Oncol, 2019. 5(3): p. 326-333.

18. Bachmann, C.L. and B. Gooch, LGBT in Britain Health Report. Stonewall. 2018. Available from: https://www.stonewall.org.uk/system/files/lgbt_in_britain_health.pdf.

19. Ameneshoa, K., LGBTQ+ staff and patients deserve better from the NHS. The King's Fund Blog, 15 February 2023. Available from: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/insight-and-analysis/blogs/lgbtq-staff-patients-deserve-better.

20. Tel Aviv University, People With Autism Experience Pain at a Higher Intensity. Neuroscience News, 29 January 2023. Available from: https://neurosciencenews.com/asd-pain-22394/.

21. Hoffman, T., et al., Indifference or hypersensitivity? Solving the riddle of the pain profile in individuals with autism. Pain, 2023. 164(4): p. 791-803.

22. Failla, M.D., et al., Increased pain sensitivity and pain-related anxiety in individuals with autism. Pain Rep, 2020. 5(6): p. e861.

Based in the north of England, Suzanne Elvidge is a freelance medical writer with a 30-year experience in journalism, feature writing, publishing, communications and PR. She has written features and news for a range of publications, including BioPharma Dive, Pharmaceutical Journal, Nature Biotechnology, Nature BioPharma Dealmakers, Nature InsideView and other Nature publications, to name just a few. She has also written in-depth reports and ebooks on a range of industry and disease topics for FirstWord, PharmaSources, and FierceMarkets. Suzanne became a freelancer in 2006, and she writes about pharmaceuticals, consumer healthcare and medicine, and the healthcare, pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries, for industry, science, healthcare professional and patient audiences.

Contact Us

Tel: (+86) 400 610 1188

WhatsApp/Telegram/Wechat: +86 13621645194

Follow Us:

Pharma Sources Insight January 2025

Pharma Sources Insight January 2025