Tim FreemanFebruary 21, 2020

Tag: Freeman Technology , Powder Flow , Powder Testing , tablet manufacture

Related reading: Powder Flow: Powder testing techniques for tablet manufacture (2)

Medications in solid dosage form continue to be universally popular, with the majority of pharmaceutical actives still delivered as tablets. Across the globe, tablet manufacturers employ a diverse range of machinery based on designs whose roots can be traced to equipment developed over a century ago. Today’s state-of-the-art tablet presses produce up to a million tablets per hour, but whatever the scale of operation or the machinery used, the fundamental challenges remain the same. Successful tablet manufacture relies on filling a die with a uniform, loosely packed blend and then compressing that powder to form a consistent stable product.

Apart perhaps from a final coating step followed by packaging, tablets are usually the end product of the manufacturing process. This is an important point when considering process optimization as many of the steps in the process are carried out with the aim of delivering a suitable feed blend to the tablet press. These steps may include feeding, screening, mixing, granulation, drying, milling, classification and lubrication.

Variations in any of these unit operations, or indeed variation in the raw materials, can have a contributory effect on the properties of the feed to the tablet press and consequently, may impact on the efficiency of the process. A greater understanding as to which powder properties relate to performance in the press, and indeed which upstream processes are most influential, enables improvements to be made at the appropriate processing stage(s). This leads to improved throughput and enhances the quality of the finished product.

In this article we examine the tableting process, from blend discharge from the feed hopper to ejection of the tablet, and consider the different conditions to which the powder is subjected. Building on this analysis we discuss which powder properties are important in defining performance at each point, highlighting the need to measure variables that accurately reflect likely powder behavior in the process. Included in the article are data that show how different techniques such as tapped density and shear testing, while valuable for specific applications, are less relevant to certain aspects of process behavior.

Preparing a tableting blend

In tablets, the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) is often only a tiny proportion of the finished product. The steps that precede the tablet press are designed to incorporate the API within a blend that processes efficiently to produce tablets of the required quality. Ingredients normally include excipients and fillers as well as components that play a more active role in product performance, such as glidants to improve powder flow and lubricants that prevent adherence to the press.

These raw ingredients may be screened, granulated, dried, milled, classified and blended, in isolation or in combination, to produce feed for the tablet press. Usually this involves a number of steps and batch processing is common, where a defined amount of material is processed then tested to confirm its suitability for the next step.

Each ingredient and unit operation is a potential source of variability arising from any number of factors including1:

Within the pharmaceutical industry, materials are tested after each processing step with the aim of quantifying variability, but this raises the question of how to characterize ‘in-process’ materials to ensure success. The tablet press is at the end of the line so any sources of variability along the way will tend to act cumulatively at this point.

The effective management of variability relies in the first instance on being able to detect a problem. This means that the specification used to define acceptability – in a feed or after a processing step - must reliably identify a material that will fail to process as required in a subsequent step, and/or go on to produce a substandard product. The implication of this is that such specifications must be based on properties that closely correlate with the aspects of performance that are critical to success. Applying this approach throughout the process, and to the feed blend, is important when optimizing throughput and product quality. It relies, however, on identifying and measuring powder properties that have a defining influence on the efficiency of the operation and the quality of the final product.

Analyzing the tableting process

Powder behavior is influenced by an array of different variables, from primary parameters such as particle size and shape to system factors such as extent of consolidation and aeration. This complexity makes it difficult to predict behavior, or even to reliably infer performance from test data acquired under conditions that are not representative of those applied during processing. To develop a secure basis for process optimization it is necessary to select characterization techniques that simulate the process environment.

Manufacturing tablets from a blend tends to be a single integrated process. However, closer analysis reveals four distinct stages, particularly in terms of the conditions applied to the powder. These are:

Tablet manufacture begins with discharge of the blend from the hopper, at a consistent, controlled flow rate. Material flows under gravity, at relatively low flow rates, into the feed frame. In the hopper itself, moderate stress is imposed by the weight of the stored powder. This can cause sufficient consolidation to inhibit flow, either because of interactions between the vessel and powder or as the result of powder-powder interactions. Cohesivity and shear strength are therefore highly relevant powder properties.

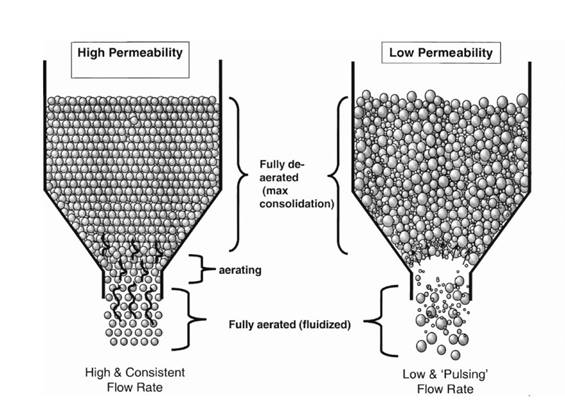

The need for containment means that the hopper discharge is routed to the feed frame via enclosed pipe work. The ease with which the blend flows under gravity is important here but so too is the permeability of the powder2. A blend with low permeability that resists the backflow of air necessary for smooth flow will tend to ‘slug’ into the feed frame (see figure 1). This can result in erratic pressure in the feed frame which varies at such a high frequency that the tablet press control system cannot adequately compensate. This in turn results in variability in the weight of the resulting tablet. In contrast, more permeable blends tend to exhibit more consistent flow, ultimately delivering a more uniform product.

Figure 1: More permeable powders tend to flow consistently from a hopper while those that are less permeable can give rise to a low rate, ‘pulsing’ flow that is detrimental to process efficiency and product quality.

In the feed frame powder is swept into the dies to ensure a complete fill. Here the blend is moderately to loosely packed but sheared at relatively high speeds as the blades of the frame rotate. Agglomeration and attrition are both potential problems, exacerbated by the need to recycle powder around this part of the process. Both can lead to segregation of the blend, giving rise to non-uniformity in the finished tablet, and attrition additionally gives rise to dusting, creating fines that go onto compromise processing efficiency and the properties of the finished tablet.

In the feed frame the powder is flowing under gravity but depending on the design of the blades there may also be a significant element of ‘forced flow’. Angling the sweeping blades can help to force the powder down into the dies, improving filling efficiency but this depends on the properties of the powder. Optimizing the flow regime in the feed frame is beneficial for consistency and the rate of die filling but this relies on understanding how the powder flows under different conditions and in particular the material’s response to forcing conditions.

The production of a uniform tablet relies on consistent die filling. The preceding discussion highlights the importance of flow properties within this context but in addition the response of the powder to air is critical. A permeable blend that quickly releases entrained air will settle rapidly and efficiently fill the die. Conversely, air can provide lubrication and promote flow in the feed frame. Therefore, a material that releases air too easily may not flow consistently. Understanding exactly how the powder responds to air can therefore be critical in optimising this part of the process.

During the final compression step the powder plug is subject to high stress. Here the compressibility of the powder is a relevant because it quantifies how the movement of the punches will impact the powder. Cohesivity is also relevant as it indicates how strongly the particles will stick together as is adhesivity; how likely it is that material will stick to the tablet press tooling. However, if a powder doesn’t flow well, it won’t fill the die efficiently and compression properties become irrelevant. Successful processing requires a powder that is compatible with all stages of the process.

Choosing the best powder characterization techniques

The example of the tablet press shows how important it can be to understand how the powder will behave under very different conditions, thereby highlighting the limitations of applying a single powder testing technique. Historically the pharmaceutical industry has relied on parameters such as Hausner Ratio and Carr’s Index, both derived from tapped density techniques, and more recently shear testing. These approaches do have some relevance when trying to access information to support optimization of the press.

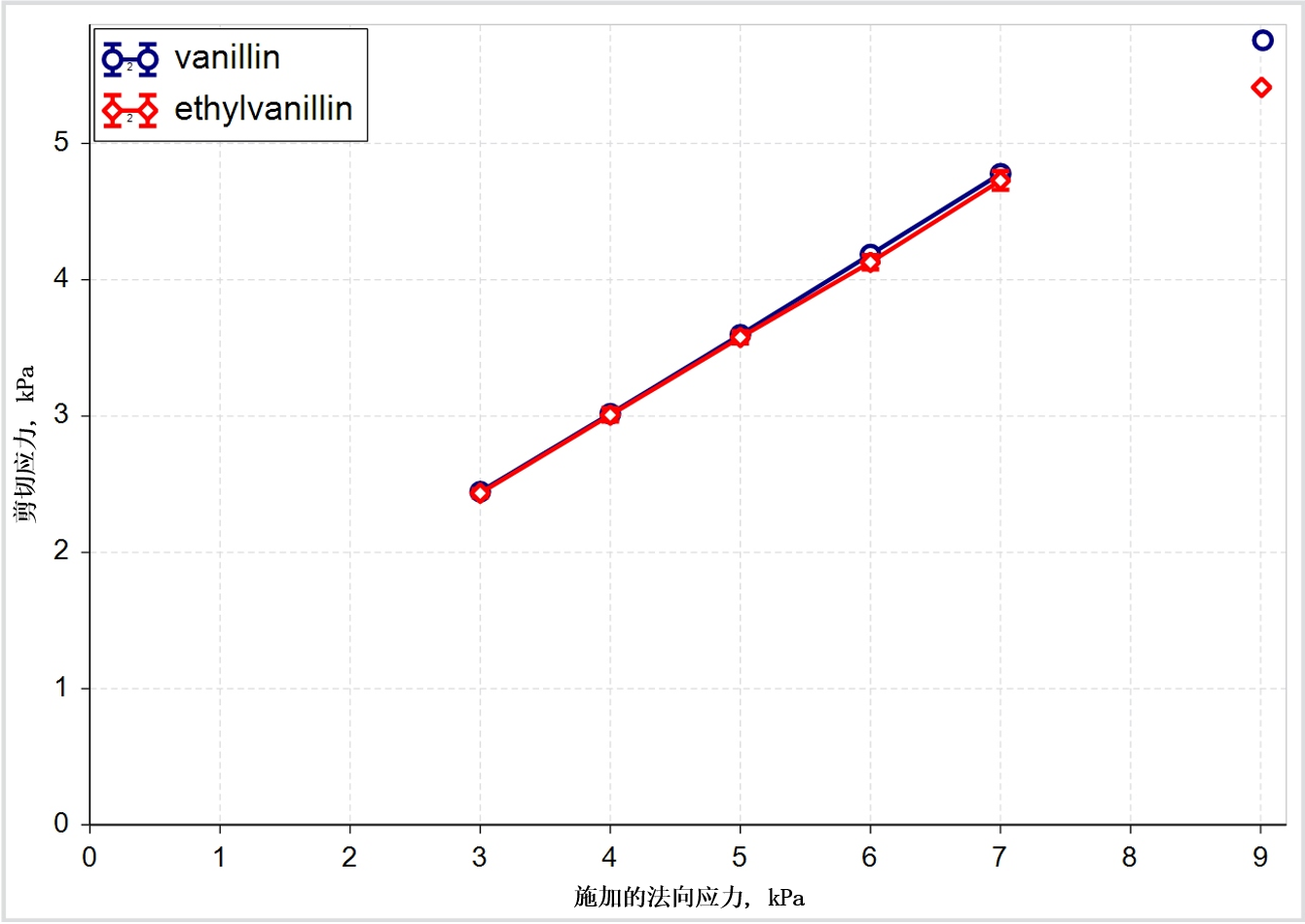

Shear testing, for example, was developed, and remains widely used, for the design and troubleshooting of hoppers. It provides valuable shear strength data that is relevant to design and operation of the feed hopper, and also to the compression stage where applied stresses are even higher. However, as the data in Figure 2 shows, shear testing may be less useful than other techniques for generating data to support other parts of the tablet manufacturing process, where applied stresses are far lower.

Figure 2(a) + 2(b): Shear data classifies these two excipients as closely similar while flow energy measurements show that in certain circumstances they can behave quite differently

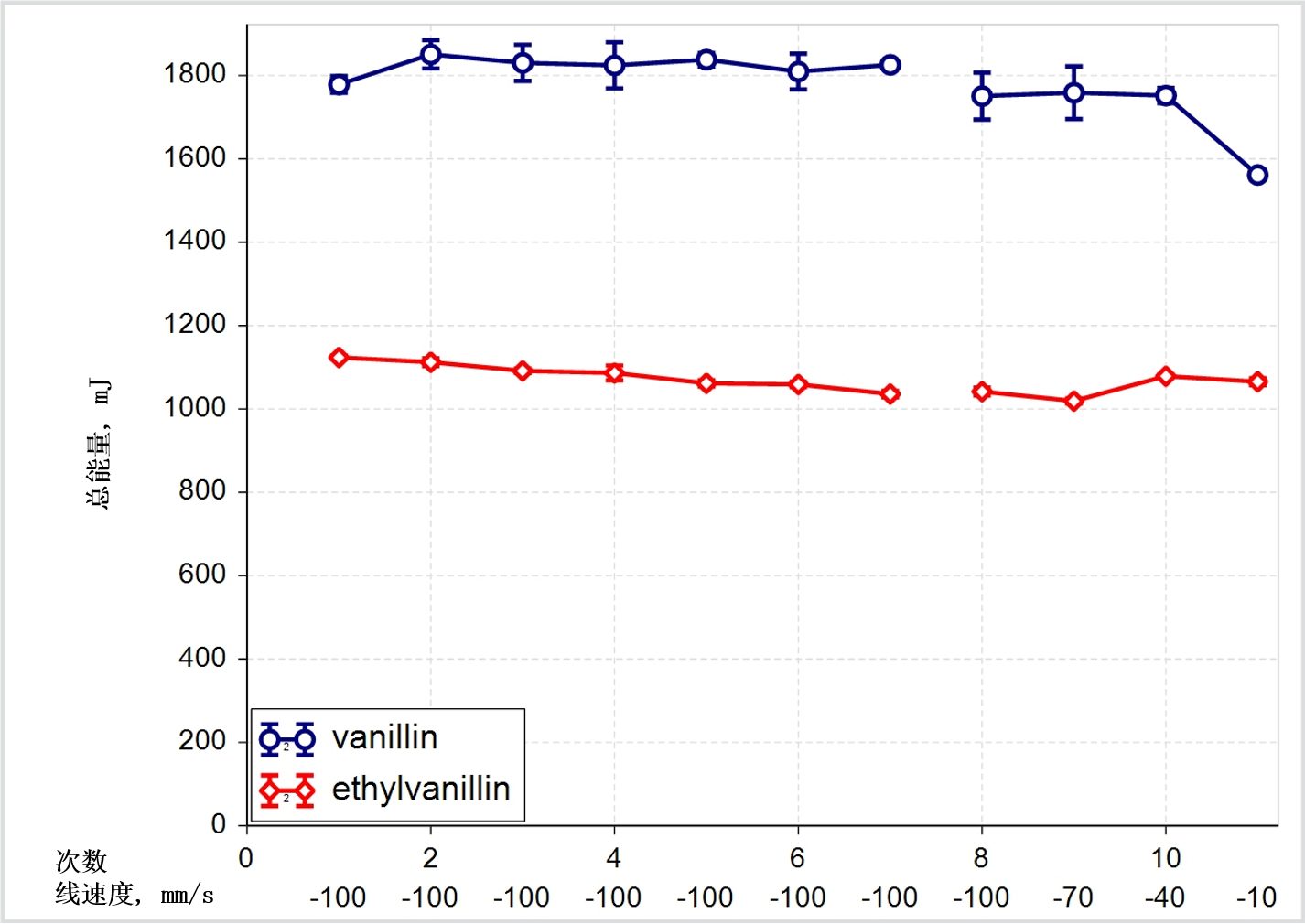

The shear data presented for vanillin and ethylvanillin classifies them as closely similar but the dynamic flow energy measurements tell a different story, suggesting that the materials can behave differently in certain circumstances. Flow energies are generated by measuring the axial and rotational forces acting on a blade as it rotates through a powder sample3. Downward rotation of the blade imposes a forcing, bulldozing action while an upward traverse measures a flow energy more closely associated with gravity induced flow.

Here then the data suggest that while these two materials may behave similarly in the hopper, and in terms of how they cohere in the finished tablet, they will behave very differently in the feed frame. The ease with which the materials flow into the feed frame, and subsequently into the die, as well as their response to a range of blade designs, are all likely to be different.

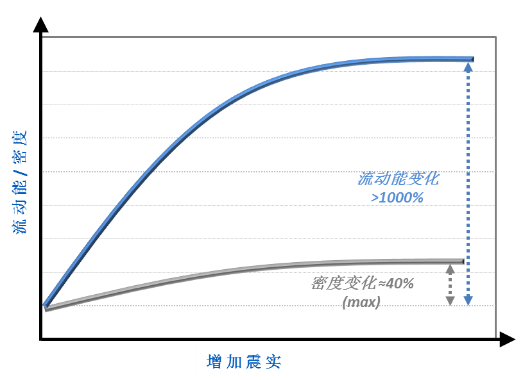

This comparison raises the question of how useful other techniques that are routinely used to investigate and compare flow might be for this application. Figure 3 contrasts tapped density measurements with flow energy data.

Figure 3: For this system tapped density data are far less sensitive than flow energy measurements in the detection of changes in powder flowability

These results show that although the tapped density measurements do detect changes that indicate differences in powder properties, they are far less sensitive than dynamic techniques in specifically measuring flow properties. Tapped density measurements could therefore fail to detect variability in a material that would go on to impact flow behaviour in the tablet press.

Looking across the tablet making process in its entirety highlights the range of properties that could advantageously be measured to optimize performance at each step. These include:

· Shear properties – for the design and troubleshooting of hoppers as well as the development of a formulation with sufficient cohesivity to form a stable tablet under specific compression conditions.

· Bulk properties such as permeability and compressibility – to assess the response of the powder to air, the ease with which displaced air will be dispersed, and how the blend will be impacted by compression.

· Dynamic properties that directly quantify flowability under different conditions – for optimising flow through the feed frame, assessing the impact of different paddle designs, investigating the effect of air on powder flowability and to quantify de-aeration behaviour. Dynamic testing can also be used to assess powder stability and is therefore a useful tool for investigating the likelihood of attrition, segregation and/or agglomeration.

Together these measurements form a database of properties that can be used to tightly define an optimal blend specification. Furthermore, such data would support investigation into which parameters in upstream processes ultimately dictate performance in the press and the quality of the final product. Such strategies are highly beneficial in pushing towards more efficient manufacture on the basis of secure knowledge.

In conclusion

Within the pharmaceutical industry there is increasing emphasis on processing efficiency and more effectively controlled manufacture. In production it is impossible to eliminate all the possible sources of variability but it is feasible to compensate for them and control their impact. This relies on identifying, measuring and controlling those parameters that define processing efficiency and the quality of the finished product.

In solid dosage manufacture achieving this goal requires a relevant and sensitive powder testing toolkit capable of reliably generating parameters that can be directly correlated with process performance. Key to this is the ability of a technique to effectively simulate the specific processing environment, which, as an analysis of tableting reveals, can vary considerably. Within this context instruments that combine established techniques such as shear and bulk property testing, with newer methodologies with proven value such as dynamic testing, are especially valuable. By presenting a selection of techniques such systems allow the user to closely tailor testing to the specific application and access the best information for process design, optimisation and control.

Author Biography

Tim Freeman, Managing Director, Freeman Technology

Tim Freeman is Managing Director of powder characterisation company Freeman Technology for whom he has worked since the late 1990s. He was instrumental in the design and continuing development of the FT4 Powder Rheometer® and the Uniaxial Powder Tester. Through his work with various professional bodies, and involvement in industry initiatives, Tim is an established contributor to wider developments in powder processing.

Tim has a degree in Mechatronics from the University of Sussex in the UK. He is a mentor on a number of project groups for the Engineering Research Center for Structured Organic Particulate Systems in the US and a frequent contributor to industry conferences in the area of powder characterisation and processing. A past Chair of the American Association of Pharmaceutical Scientists (AAPS) Process Analytical Technology Focus Group Tim is a member of the Editorial Advisory Board of Pharmaceutical Technology and features on the Industry Expert Panel in European Pharmaceutical Review magazine. Tim is also a committee member of the Particle Technology Special Interest Group at the Institute of Chemical Engineers, Vice-Chair of the D18.24 sub-committee on the Characterisation and Handling of Powders and Bulk Solids at ASTM and a member of the United States Pharmacopeial (USP) General Chapters Physical Analysis Expert Committee (GC-PA EC).

Keep Reading:

Powder Flow: Powder testing techniques for tablet manufacture (2)

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

Editor's Note:

En-CPhI.CN is a vertical B2B online trade platform serving the pharmaceutical industry,

for any copyright disputes involved in the reproduced articles,

please email: Julia.Zhang@ubmsinoexpo.com to motify or remove the content.

Contact Us

Tel: (+86) 400 610 1188

WhatsApp/Telegram/Wechat: +86 13621645194

Follow Us:

Pharma Sources Insight January 2025

Pharma Sources Insight January 2025